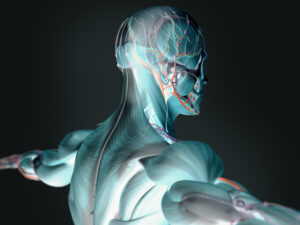

‘The body – the cage – is everything of the most respectable – but through the bars, the wild animal looks out.’ (Mr Ratchett in Murder on the Orient Express, by Agatha Christie)

An odd idea, you may think. But how many of us have been transported to another world by reading a novel, have basked in the comfort it gives us as we curl up to read, or have held it by the hand as it takes us on wild adventures and dangerous missions? And when the reading of that novel is complete, how many of us have grieved for the story, missed the experience it gave us? In short, for the time we spent invested in that book, it became our friend. So it’s not too far a stretch to think of the novel as a living, breathing human.

A novel is, at its heart, an idea or theme, and the story is its lifeblood. Imagine a story with a transformative theme of love, about a girl (let’s call her Lucy) who grows up, is frustrated in relationships, and eventually enters the religious life. Those are the bones of the story. The lungs and nervous system are made up of Lucy’s personality traits, both positive and negative, as seen through the pages of the book, her direct and indirect thought, and the dialogue she engages in with other characters. The muscle of the book is formed by the characters that surround Lucy and her relationships with them. The story is fleshed out by what she does and where she goes, and the rising and falling action of the novel itself.

If the book includes a lot of background detail and historical backdrop, without giving the reader access to Lucy’s feelings and without showing her interactions with other characters and her reactions to their activity – basically, with a lot of exposition – then much of the body is missing. Don’t get me wrong; a story needs an environment, a grounding, a setting, if you like, but to continue the analogy, those are the factors that would form the clothing and home of the story. Without the flesh and blood, the story becomes an outfit on a coat hanger without the body to fill it out. If you were at a social gathering of a dozen or so people, and in a corner was a coat stand, you might glance at it, admire the coat hanging from it, but you wouldn’t engage with it.

Many new authors spend a great deal of time and intellectual effort in research and are anxious to get that down on paper and ensure it forms part of their book, sometimes to the detriment of the central theme and story. As I once heard Emma Darwin say, ‘Don’t let the research tail wag the story dog’! Research is vital (otherwise you might end up with characters in the reign of Elizabeth I celebrating Guy Fawkes Night), but remember that your book is about your characters and not an essay on the researched facts.

new authors spend a great deal of time and intellectual effort in research and are anxious to get that down on paper and ensure it forms part of their book, sometimes to the detriment of the central theme and story. As I once heard Emma Darwin say, ‘Don’t let the research tail wag the story dog’! Research is vital (otherwise you might end up with characters in the reign of Elizabeth I celebrating Guy Fawkes Night), but remember that your book is about your characters and not an essay on the researched facts.

Perhaps I’m taking the analogy too far. What I’m really asking you, the author, to do, is to think about how you can narrow the distance between the narrative and the reader, the characters and their setting. Make the characters part of your environment; make them live in the history in which the story is set, rather than be buried underneath it.

Have a look at this article, which will tell you more about showing vs telling, and how you can be sure you will draw your readers in to engage with your novel, rather than remind them they’re being told a story.

Perfect the Word: polishing your prose; keeping it yours.